Memory Vistas

How a conversation turned into a collaborative reimagining of our family history

My brother and I talked about collaborating for years. We talked about it in the way you might talk about having dinner at a popular restaurant on the other side of town—yes, we should, we really should—both of us hopeful but doubtful it would ever happen. In some ways, collaboration always seemed natural, an inevitability even. He’s a photographer; I’m a writer. Still, it was always: Yes, we should, but when and on what and how? I can’t speak for him, but I was afraid I’d let him down. His faith in me had always been limitless, and I didn’t want to lose that.

Kyle likes to go on long drives with his camera, always heads west from home because west has been lucky for him. I understand superstitions like this; writers are full of them. I started going, too, just to keep him company, and then I started to bring a notebook. Our conversations about collaborating suddenly seemed less hypothetical—just because of the notebook I carried. But I was hesitant to put it to use. I didn’t know how to work when I wasn’t alone. Writing is a joyous pursuit, but it is also isolating and sometimes lonely. In other words, I might have been the one in need of company.

On one of our drives, Kyle and I parked and strolled down the main street of a small town that was experiencing revival and everything that comes with it—craft beer, patio lights, and the sound of distant hammering in all directions, a constant call and response. There was an industrial building—quiet on a Friday afternoon, suggesting obsolescence—and behind it, a metal staircase that led to a parking lot situated far below.

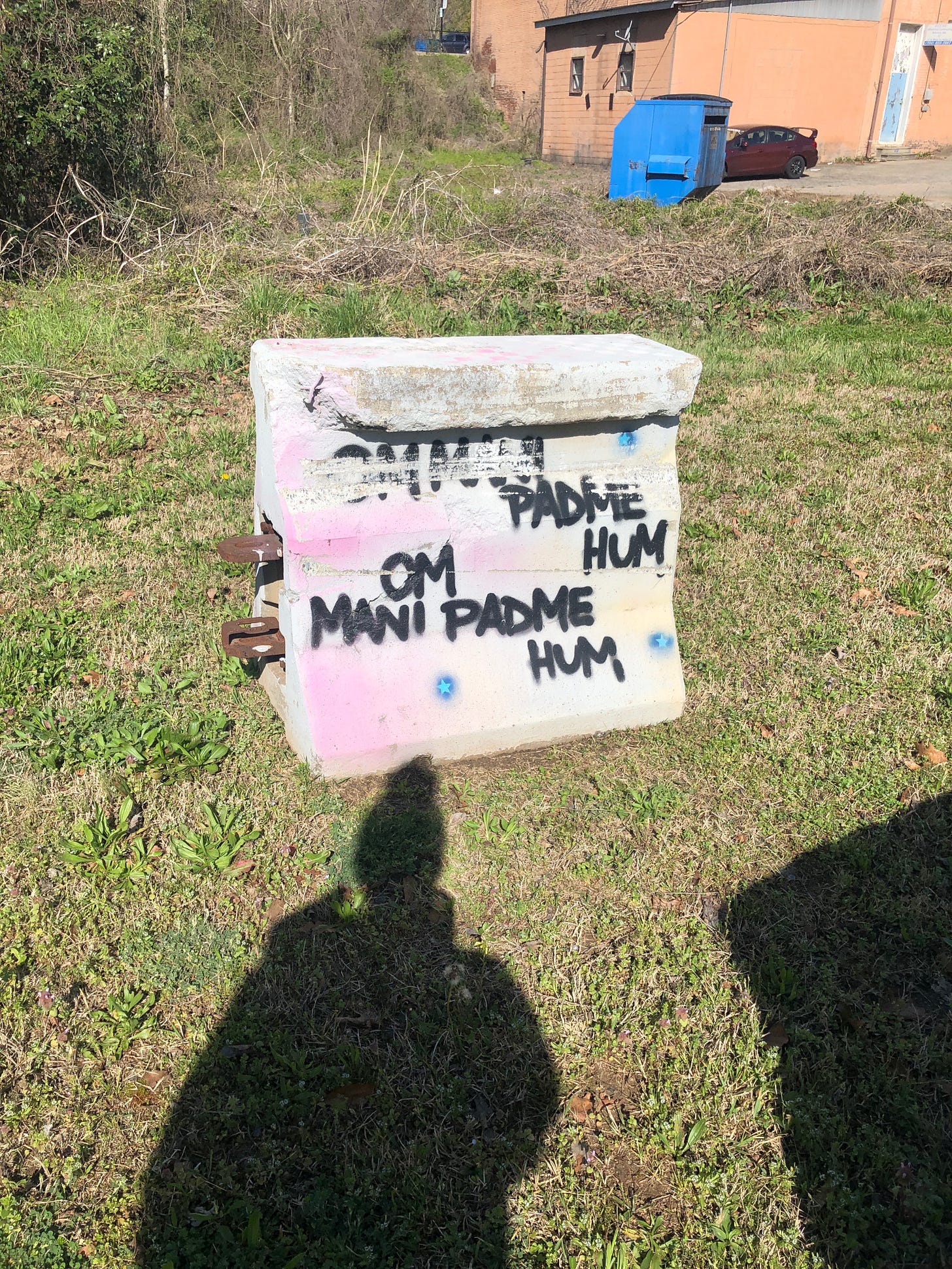

Rows of large concrete blocks were lined up in the grass that edged the parking lot. I didn’t have a name for what they were or an understanding of what they might be used for. They were painted in bright colors. There were polka dots and stars. A sunset gradient. A peacock’s feather. Fish scales. There were words on two of them. One said, “I <3 men.” The other, “Om mani padme hum. Om mani padme hum.”

Because of the way the blocks were so evenly spaced apart, they reminded me of headstones. This impression was bittersweet since they’d been painted by someone wanting to leave a mark. This interested me. I made notes. I copied down the phrase “Om mani padme hum.” I tried and failed to interpret the words, enchanted by the way they repeated on the concrete, the way they begged repetition in my mind.

When I looked up from my notebook, I saw Kyle at the top of the metal staircase, his camera aimed at the industrial building. He was so far away from my brightly painted graveyard. Realizing it would not appear in any of his photographs, I started snapping pictures with my phone so I’d have images I could reference later, still believing the story I’d write would be related to his photographs. As I took my pictures and Kyle took his, we had our backs to one another. To say something to him, I would’ve had to yell. He was up high. I was down low. I thought, “I might not be capable of collaboration.” After all, what if I simply had nothing to say about the building at the top of the stairs?

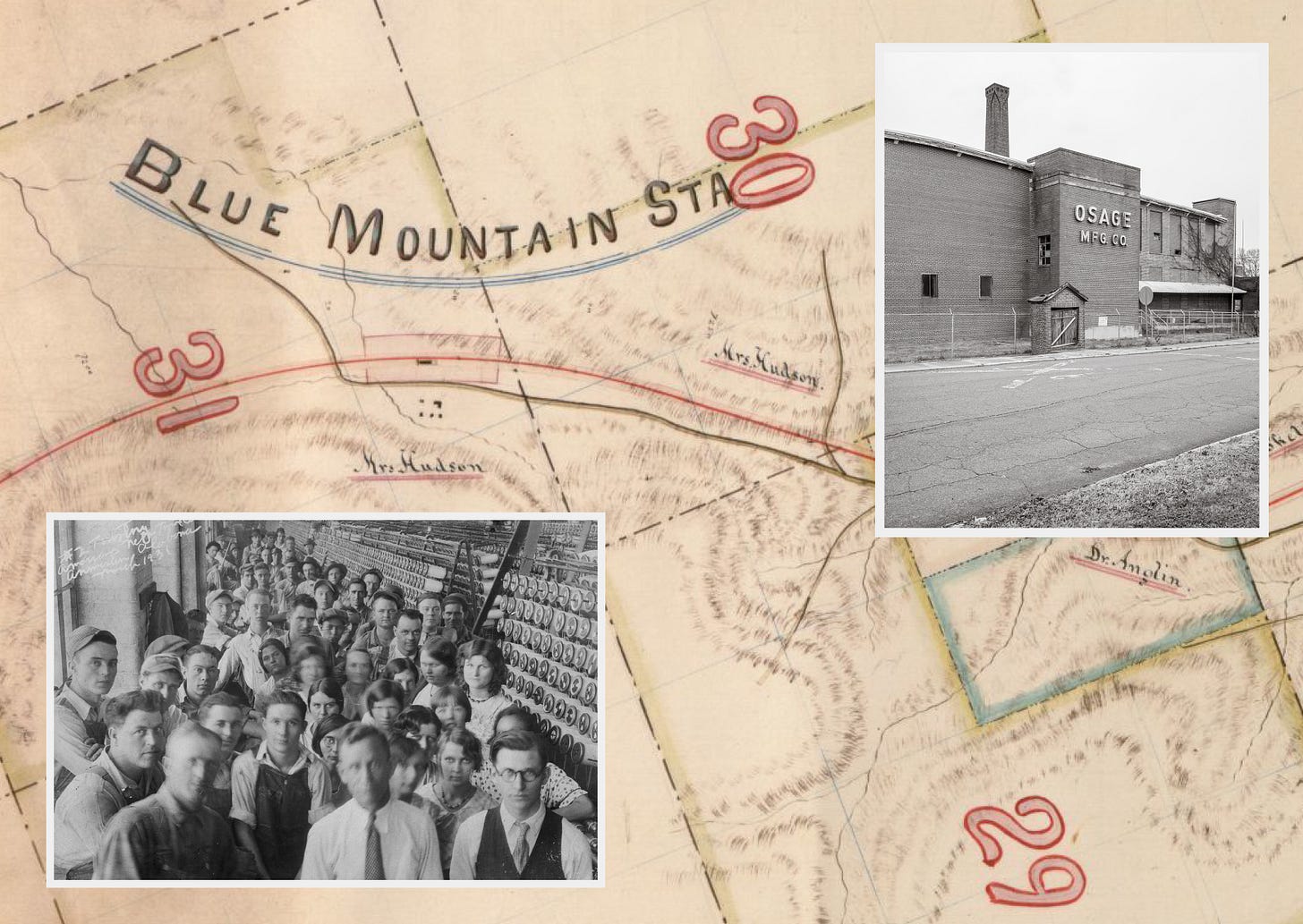

On our way home, we stopped to buy peaches at a peach stand and talked about how the land our mother grew up on was once an orchard. In fact, the Foothills of North Carolina looked a lot like Northeast Alabama, the industrial building some version of the old linen thread mill in Blue Mountain. The conversation kept circling back to our grandmother. “Do you think you’re telling her story with these photographs?” I asked. I knew my grandmother’s voice. I knew it like a heartbeat thrumming in my own chest. I could write that voice.

He said, “Yeah,” with confidence, as if he’d known it all along. Just like that, we had a subject for our first project, which would become Dark Water Lavender, and we knew we’d go on mining our family history for a while, that there would be other sources of inspiration, possibly an endless supply.

Back on the highway, I noticed the concrete barriers between lanes as if for the first time and recognized their shape. I looked at the pictures of my dayglow headstones and realized they were highway dividers, objects I’d seen countless times but had not recognized out of context.

Maybe it was seeing those inscrutable words on the concrete that had turned them, as if by magic, into something new and beckoning. When I looked up the meaning of Om mani padme hum, I was embarrassed I’d been unaware of something so important in so many cultures. I learned the mantra was more of a spiritual practice than an idiom that could easily be translated into English, but that its message was one of compassion.

In a place we had no factual connection to, we’d encountered our loved ones, our shared and inherited memories. They were there, taken out of the context of time and place. But in a new context, we realized we might see them afresh. There was, of course, a divide between the past and present, a divide between a person’s truth and what anyone could possibly know of it. And there would always be a divide between Kyle’s work and mine. These spaces, though, are not empty. They are filled with stories.

Collaboration is akin to compassion. Maybe these two words are of the same spiritual practice. They both ask us to step over the barriers we’ve put up around ourselves, but in exchange for this, we’re able to enter a space where we’re not alone.

Memory Vistas is a long overdue collaboration, but maybe it’s also a spiritual practice.

Pursuing the stories that exist somewhere between fact and fiction, between the past and present, we happily leave ourselves behind and come closer to what we share.

Through a series of projects that combine text and image, we will share our family history and family lore, the real and imagined stories that were inspired by the people and places we love.

We hope you’ll join us for the ride. Who knows? Maybe you’ll find pieces of your own past along the way.